One of my resolutions for 2025 was to really dive into a branch of philosophy. I’m talking full-on, head-first, no-looking-back kind of dive. I landed on Existentialism. Why? Well, for starters, “existential” is a word I’ve been throwing around ever since I discovered it. Whether I’ve been using it correctly is… questionable at best.

Second, I’ve always found people who can talk philosophy on a deep level wildly fascinating. I want in on that. I want to be one of those people.

And third – maybe most importantly – I constantly catch myself asking, “But what does it all mean?” So yeah, existentialism felt like the right place to start.

The origins of fascination…

At its core, existentialism means “to have existence.” But what does that actually mean? My simultaneous gripe and fascination with the concept is that existentialism is, well… existential. It loops back on itself in a way that’s both confusing and kind of brilliant.

I can’t pinpoint the exact moment I first heard the word. Maybe it was at a university open day, or during an episode of University Challenge. What I do remember, though, is who made me want to know more about it. And no – it wasn’t Kierkegaard, Camus, Sartre, or Nietzsche. It was Allison Reynolds.

Who is Allison Reynolds, you ask? She’s one of the most iconic figures in ’80s cinema. To some, she’s Allison; to others, she’s the basket case – the brooding, black-clad introvert from John Hughes’s The Breakfast Club. Never had my fifteen-year-old self felt more seen than when I watched that movie for the first time. More specifically, when I watched Allison.

That’s not to say Allison and I were (or are) anything alike. But her conundrum resonated with me. That mix of dissatisfaction and desire – of wanting more from the world but also not knowing what “more” even looks like – felt strangely familiar.

There’s this one scene that’s always stuck with me. Allison dumps out the contents of her bag for Brian and Andy to see. Brian asks, “Are you gonna be like a shopping bag kid?” And Allison replies, “I’ll do what I have to do.” Then Brian follows up: “Why do you have to do anything?”

Whether Hughes meant it this way or not, what comes next is one of the most quietly profound exchanges in the entire movie.

‘My home life is unsatisfying.’ (Allison)

‘Unsatisfying? You’d subject yourself to the violent dangers of the street because things are unsatisfying.’ (Brian)

‘I don’t have to run away and live on the street. I could run away to the country. I could run away to the mountains — I could run away to Afganistan.’ (Allison)

It doesn’t look like much on paper, right? But watch the movie, and I guarantee – you’ll feel something. Anyway… back to what I’m trying to say. What really struck a chord with me were two things: 1) Allison’s use of the word unsatisfying, and 2) the way she talks about running away – toward what I’ve always interpreted as something “better”. Something satisfying.

I’ve always felt moved by that scene, but it wasn’t until I entered my twenties – stepped into the so-called real world – that I started to really unpack it. My home life couldn’t be more different from the one Allison hints at, and I’ve never had the urge to flee to Afghanistan. No, where she and I connect is in this deep, unshakable feeling of never being fully satisfied. In that shared belief that there’s a vast world waiting to be discovered. But that’s exactly where the trouble begins.

Before she ever dared step outside her comfort zone, eighteen-, nineteen-, even twenty-year-old Ellen was perfectly content. Reading books in the safety of her childhood bedroom. Writing papers on Dickens and Fitzgerald. Making the same, simple meals for breakfast, lunch, and dinner. Living by a carefully crafted routine.

But the moment she decided to leave home, everything shifted. She traded routine for spontaneity. Swapped predictability for the unknown. And in doing so, she let go of comfort and ‘satisfaction’ for something far more elusive – a longing for the indefinable.

Defining the ‘indefinable’…

Over the past few years, travel – both the act and the idea of it – has become a constant presence in my life. Social media, especially, has made it seem accessible to almost everyone. One minute, you’re scrolling through Instagram, watching someone dive off a cliff somewhere in Southeast Asia. The next, you’re drooling over someone’s “Everything I Ate In X, Y, Z” reel. Travel content is everywhere.

And honestly? I love it. I’ve tried to engage with it in my own way. But I can’t ignore how it also contributes to a quiet, creeping dissatisfaction – especially for those of us prone to overthinking. It convinces us that what’s right on our doorstep isn’t enough. That simply waking up, making coffee, and going to our 9-5 is somehow too ordinary for the world we live in now.

I think it all started in Venice (everything started in Venice…) – when I began filming people being, well, people. People walking, talking, pausing to look at the water. That simple act became a habit. I still do it. And what I’ve gained from it is this overwhelming sense that everyone – everyone – has a story to tell. It’s so powerful, it sometimes brings me to tears. The realisation that we’re all just trying to find our way through life. Trying to navigate it, and inject meaning into it.

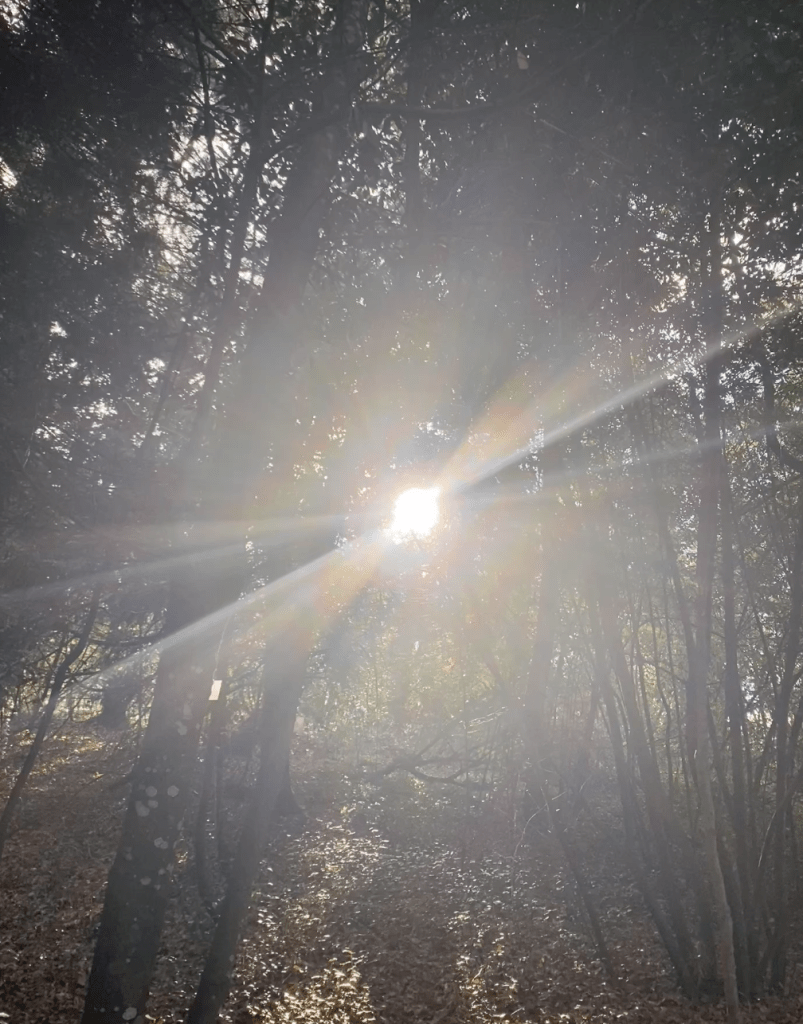

Defining the “indefinable” in Italy meant doing as the Italians do: wandering without a purpose; sipping wine at 5pm; greeting the local nonni with a “buongiorno” or “buonasera”; eating good food and refusing to feel guilty about it. It was about savouring the small pleasures. Slowing down enough to watch life unfold, softly.

In Portugal, defining the “indefinable” meant something slightly different: embracing the charm of small-town life; getting to know locals, not just in passing, but deeply; sitting in the quiet hush of a Sunday morning; letting the sun daze me into stillness. It was about appreciating the virtues of simplicity – of living humbly, and wholeheartedly.

Now that I’m back in the UK, with travel plans on pause, defining the “indefinable” has become harder. And so, we circle back to Existentialism. To the aching question that hums beneath everything: what gives life its meaning?

Finding meaning in an otherwise “meaningless” world…

If you think about it, it makes total sense that existentialism is so often associated with anxiety. Anyone who’s even dipped a toe into the theory has had to confront the idea that we live in an inherently “meaningless” world. Scary stuff, right?

So how do we even begin to tackle that? How does one manage the overwhelming responsibility to create something exceptional in an otherwise “unexceptional” world? Well, we can start by resisting the urge to compare.

One of life’s few absolutes is this: someone else will always have it better. One person is sitting at their desk contemplating a meal deal, while another is sipping limoncello in Positano. One person is mastering their fifth language, while another is waiting for their hearts to refill on Duolingo. Whether we like it or not, there’s always someone who appears to be doing more. Or so we think.

Here’s something I’ve learned over the past few years: to compare is to lose – every time. Why? Because my life is just that – mine. Existentialism resonates with me now more than ever because I exist in a society built to make me want. It urges me to crave more without ever clarifying what “more” actually means. Yes, I want to see more of the world. I want to have a job I love. I want time to nurture my passions. I could list a hundred things I want, and still, I’d be left… wanting. And why is that? Is it burning ambition – or quiet dissatisfaction?

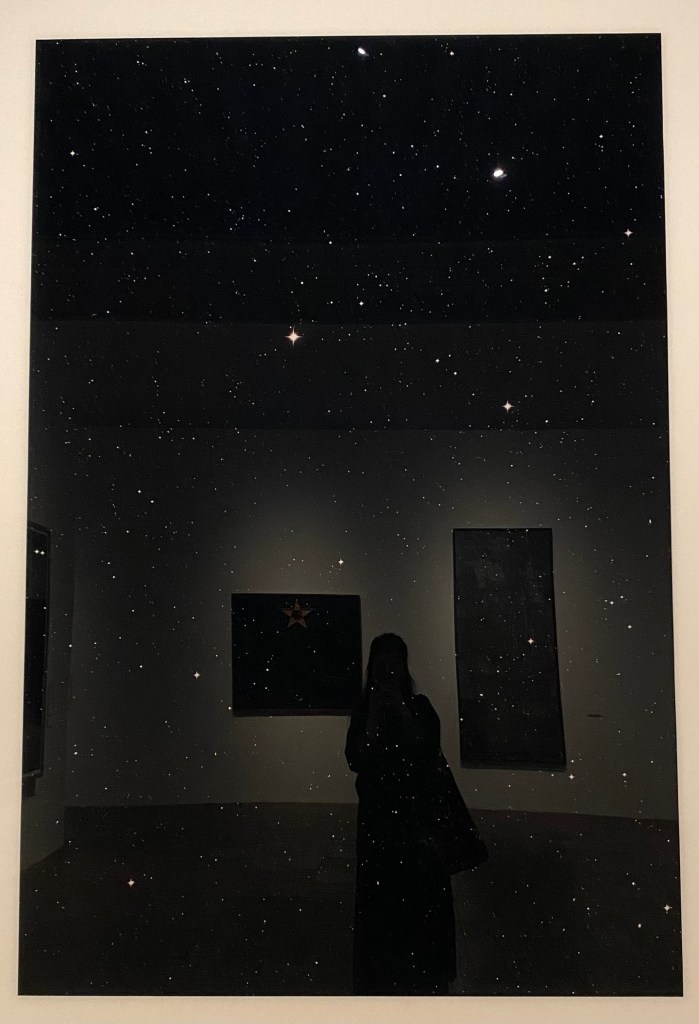

I’d love to say it’s the former. But it’d be pretty naive to ignore what is, essentially, the heart of this whole reflection. To be human is to be both ambitious and dissatisfied. Why? Because the moment we become conscious, we’re seduced by infinite possibilities. We look at pictures, read about distant lands, stand in front of art, and tilt our heads at relics from the past. To be human is to be aware of what exists but isn’t readily accessible. In short, to be human is to be overwhelmed. But that’s okay. That’s life.

Where Allison, existentialism, and I meet today is here: wanting more doesn’t mean you’re miserable. Quite the opposite. Isn’t the point of life to want? The way I see it, the day we stop wanting is the day we stop breathing. I don’t know if Allison made it to the country or the mountains. That’s not the point. The point is that she wanted to. That even in her sadness, even in her loneliness, she held on to something – an idea, an abstract hope – that kept her going.

We live in an age where life moves at a thousand miles an hour. Where everyone seems to be doing something extraordinary. Where ambition and dissatisfaction blur into one. A confusing age, to put it lightly. But for me, diving into existentialism isn’t about finding answers. It’s about asking better questions, feeding my curiosity, and – more than anything – continuing to want.

Because honestly, can you imagine having all the answers? Can you imagine never striving for something, not necessarily better, but something, different? What a dull existence that would be.

To Be Great, Be Entire – Fernando Pessoa

To be great, be entire: of what’s yours nothing

Exaggerate or exclude.

Be whole in each thing. Put all that you are

Into the least you do.

Like that on each place the whole moon

Shines, for she lives aloft.

(14.2.33)

Leave a comment